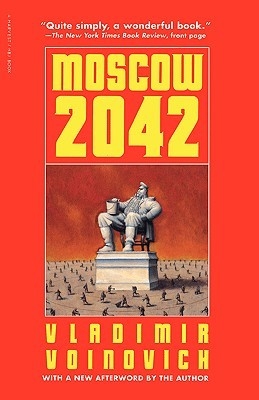

The novel covers the years 1711-1720. The epistolary form of the work and additional piquant material from the life of Persian harems, a peculiar construction with exotic details, full of bright wit and caustic irony of description, well-defined characteristics made it possible for the author to interest the most diverse audience up to and including court circles. During the life of the author, “Persian Letters” were published in 12 editions. The novel solves the problems of the state system, questions of domestic and foreign policy, questions of religion, religious tolerance, a decisive and bold shelling of autocratic rule and, in particular, the mediocre and extravagant reign of Louis XIV. Arrows fall into the Vatican, ridiculed by monks, ministers, the whole society as a whole.

Uzbek and Rika, the main characters, Persians, whose curiosity forced them to leave their homeland and go on a journey, conduct regular correspondence both with their friends and among themselves. An Uzbek in one of his letters to a friend reveals the true reason for his departure. He was introduced to the court in his youth, but this did not spoil him. Exposing a vice, preaching the truth and preserving sincerity, he makes a lot of enemies and decides to leave the yard. Under a specious pretext (study of Western sciences), with the consent of the Shah, Uzbek leaves the fatherland. There, in Ispahani, he owned a seraglio (palace) with a harem, in which were the most beautiful women of Persia.

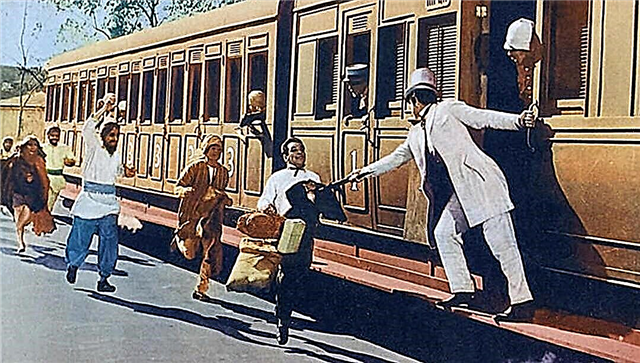

Friends begin their journey with Erzurum, then their path lies in Tokatu and Smyrna - lands subject to the Turks. The Turkish empire is living at that time the last years of its greatness. Pasha, who receive their posts only for money, come to the provinces and rob them like conquered countries, soldiers submit exclusively to their whims. Cities depopulated, villages devastated, agriculture and trade in complete decline. While the European nations are improving every day, they perish in their primitive ignorance. In all the vast expanses of the country, only Smyrna can be considered as a city rich and strong, but Europeans make it that way. Concluding the description of Turkey to his friend Rustan, Uzbek writes: "This empire, in less than two centuries, will become the theater of triumphs of some conqueror."

After a forty-day voyage, our heroes end up in Livorno, one of the most prosperous cities in Italy. The Christian city seen for the first time is a great sight for a Mohammedan. The difference in buildings, clothing, main customs, even in the slightest trifle is something unusual. Women enjoy greater freedom here: they wear only one veil (four Persians), they are free to go out any day accompanied by some old women, their sons-in-law, uncles, nephews can look at them, and husbands almost never take offense at it . Soon, travelers rush to Paris, the capital of the European Empire. After a month of metropolitan life, Rika will share her impressions with her friend Ibben. Paris, he writes, is as big as Ispagan, "the houses in it are so high that you can swear that only astrologers live in them." The pace of life in the city is completely different; Parisians run, fly, they would faint from the slow carts of Asia, from the measured step of the camels. The eastern man is not at all fit for this running around. The French are very fond of theater, comedy - arts unfamiliar to Asians, since by their nature they are more serious. This seriousness of the inhabitants of the East stems from the fact that they have little contact with each other: they see each other only when the ceremonial forces them to do this, they are almost unknown to the friendship that makes up the delight of life; they sit home, so every family is isolated. Men in Persia do not have the liveliness of the French, they do not see the spiritual freedom and contentment, which in France is characteristic of all classes.

Meanwhile, disturbing news comes from the harem of Uzbekistan. One of the wives, Zasha, was found alone with a white eunuch, who immediately, by order of the Uzbek, paid for treachery and infidelity with his head. White and black eunuchs (white eunuchs are not allowed to enter the harem rooms) are low slaves who blindly fulfill all the desires of women and at the same time force them to obey the laws of seraglos unquestioningly. Women lead a measured lifestyle: they do not play cards, do not spend sleepless nights, do not drink wine, and almost never go out into the air, since the seraglion is not adapted for pleasure, everything is saturated with submission and duty. The Uzbek, talking about these customs to a familiar Frenchman, hears in response that Asians are forced to live with slaves, whose heart and mind always feel the belittling of their position. What can be expected from a man whose whole honor is to guard the wives of another, and who is proud of the most heinous position that exists in people. The slave agrees to endure the tyranny of the stronger sex, if only to be able to bring the weaker to despair. “It pushes me most of all in your manners, free yourself, finally, from prejudice,” concludes the Frenchman. But Uzbek is unwavering and considers traditions sacred. Rika, in turn, watching Parisians, in one of her letters to Ibben discusses women's freedom and is inclined to think that the power of a woman is natural: this is the power of beauty, which nothing can resist, and the tyrannical power of men is not in all countries extends to women, and the power of beauty is universal. Rika notes about herself: “My mind imperceptibly loses what is still Asian in it, and effortlessly aligns itself with European mores; "I only recognized women since I was here: in one month I studied them more than I could have done in seraglio for thirty years." Rika, sharing with Uzbek her impressions of the peculiarities of the French, also notes that, unlike their compatriots, whose characters are all the same because they are extorted (“you don’t see at all what people really are, but you only see what they are they are forced to be ”), in France pretense is an unknown art. Everyone is talking, everyone is seeing each other, everyone is listening to each other, his heart is open as well as his face. Playfulness is one of the national character traits

The Uzbek talks about the problems of the state system, because, being in Europe, he has seen many different forms of government, and here it is not like in Asia, where the political rules are the same everywhere. Reflecting on what kind of government is the most reasonable, he comes to the conclusion that what is perfect is one that achieves its goals at the lowest cost: if people are as obedient with soft government as they are with strict government, then the former should be preferred. More or less severe punishments imposed by the state do not contribute to greater obedience to laws. The latter are also feared in those countries where punishments are moderate, as well as in those where they are tyrannical and terrible. Imagination itself adapts to the morals of a given country: an eight-day prison sentence or a small fine also affects a European brought up in a country with soft rule, like losing a hand to an Asian. Most European governments are monarchical. This condition is violent, and it soon degenerates into either despotism or the republic. The history and origin of the republics is described in detail in one of the letters of Uzbek. Most Asians are not aware of this form of government. The formation of the republics took place in Europe, as for Asia and Africa, they were always oppressed by despotism, with the exception of a few Asian cities and the Republic of Carthage in Africa. Freedom seems to have been created for European nations, and slavery for Asian nations.

An Uzbek in one of his last letters does not hide his disappointment from traveling in France. He saw a people, generous in nature, but gradually corrupted. An unquenchable thirst for wealth and the goal of becoming rich through not honest work, but the ruin of the sovereign, state and fellow citizens, arose in all hearts. The clergy does not stop at deals ruining his trusting flock. So, we see that, as the stay of our heroes in Europe is prolonged, the morals of this part of the world begin to seem less surprising and strange to them, and they are struck by this surprisingness and strangeness to a greater or lesser extent depending on the difference in their characters. On the other hand, as the absence of the Uzbek in the harem is dragging on, the disorder in the Asian sera increases.

The Uzbek is extremely concerned about what is happening in his palace, as the chief of the eunuchs reports to him about the unthinkable things happening there. Zeli, going to the mosque, drops the veil and appears before the people. Zashis are found in bed with one of her slaves - and this is strictly prohibited by law. In the evening, a young man was discovered in the garden of Seral, moreover, his wife spent eight days in the village, in one of the most secluded summer cottages, together with two men. Soon, the Uzbek will find out the answer. Roxanne, his beloved wife, writes a dying letter in which he admits that she deceived her husband by bribing eunuchs, and, mocking the jealousy of Uzbek, she turned the disgusting serag into a place for pleasure and pleasure. Her lover, the only person who tied Roxanne to life, was gone, therefore, taking poison, she follows him. Turning her last words in her life to her husband, Roxanne confesses her hatred for him. The rebellious, proud woman writes: “No, I could live in captivity, but I was always free: I replaced your laws with the laws of nature, and my mind always remained independent.” The death letter of Roxanne to Uzbek in Paris completes the story.